Michael Wolmetz and Debora Brakarz

Debora Brakarz asks her boyfriend, Michael Wolmetz, about the pain he felt following the death of his father; Michael then surprises Debora with a proposal using the ring his father once gave to his mother.

Originally aired February 14, 2004, on NPR Weekend Edition Saturday.

Nate and Marc Herschberg

Marc Albaum (right) asks his uncle Nate Herschberg to sing for him a popular Yiddish song that Nate’s mother used to sing for him when he was a baby.

Originally aired December 16, 2003, on NPR’s Morning Edition.

Isabel and Mary Beaton

Isabel Beaton tells her daughter, Mary, about growing up in Bronx.

Albert and Doris Kahn

Albert Kahn shared remembrances with his wife, Doris, about times spent on Coney Island and in movie houses during his childhood.

Originally aired December 16, 2003, on NPR’s Morning Edition.

Rita and Teresa Giordano

Rita Giordano and her daughter Teresa discuss the values that Rita would like to see carried forward into the future like honesty, integrity, and peace. Teresa also asks her mother how she would like to be remembered.

Originally aired December 16, 2003, on NPR’s Morning Edition.

The Last Elevator

On the morning of September 11, 2001, Michael Nestor, Liz Thompson, and Richard Tierney were eating breakfast at Windows on the World, the restaurant at the top of the North Tower of the World Trade Center. Together, they rode in the last elevator down in the moments before American Airlines Flight 11 struck the building at 8:46 that morning. Everyone at the restaurant at the time of impact, approximately 170 men and women, perished.

Recorded in New York City. Premiered September 11, 2003, on Morning Edition.

This documentary comes from Sound Portraits Productions, a mission-driven independent production company that was created by Dave Isay in 1994. Sound Portraits was the predecessor to StoryCorps and was dedicated to telling stories that brought neglected American voices to a national audience.

Seymour Rexite, The Yiddish Crooner

At the height of his popularity in the 1940s and ’50s, Yiddish crooning sensation Seymour Rexite starred on 18 half-hour radio shows a week. At its outset his career comprised an all-Jewish repertoire that spanned from liturgical song to Yiddish popular music. But when he took to the Yiddish airwaves, the bill of fare diversified. Whatever song happened to be popular on American radio, his wife, Miriam Kressyn, translated into Yiddish and Rexite sang on one of his shows. He feared nothing, sang everything, and stayed on the air for the better part of five decades.

The son of a cantor, Rexite (originally spelled Rechtzeit) started performing professionally while still in knickers — the “Wonder-Boy,” they used to call him. He hadn’t yet reached his teens when he sang before a special congressional committee and then at the White House in a bid to convince the United States government to allow his mother and sisters to emigrate from Poland. The command performance so moved President Calvin Coolidge he relented to the plea on the spot.

Rexite was equally persuasive in the many venues he came to play, from Yiddish theater, radio, recordings, and film to regular gigs in upscale New York nightclubs like Billy Rose’s Diamond Horseshoe and the Casino de Paris. Excelling in each, Rexite was poised to hone the sort of musical crossbreed that formed the foundation for some of his best remembered songs.

The blend had its roots in the 1943 marriage of Rexite and Miriam Kressyn, a popular Yiddish actress and singer in her own right. Kressyn proved an extraordinary talent at turning American standards into Jewish hits. Who could have guessed that show tunes from Oklahoma would sound so good in Yiddish?

The Kressyn-Rexite concoctions struck big with American Jews. Rexite’s smooth-as-scotch tenor won him Sinatra-like adoration from female fans. And Kressyn’s translations, always lyrical and often lampoons, pleased and surprised careful listeners. Example: “love and marriage,” in her rendition of the well-known 1955 hit of the same name, “geyt tzuzamen vi zup un knaydlakh” (go together like soup and dumplings) instead of “like a horse and carriage.”

The team’s work also translated into highly successful advertising for Rexite’s radio sponsors, which included national clients like Ajax and Campbell’s Soup. While Rexite often guest-starred on lavishly produced shows like WHN’s “Yiddish Melodies in Swing,” the programs he created, like “The Barbasol Troubadour,” were all variations on a theme: Rexite, a microphone, and a pianist/organist. His accompanists included Sam Medoff, moonlighting from his gig as bandleader of “Yiddish Melodies in Swing,” and Abe Ellstein, who composed many of his hits.

Seymour Rexite lived in lower Manhattan until his death, at the age of 91, in October 2002.

Seymour Rexite (né Rechtzeit) began his career as a child star. His solo command performance at the White House so moved President Coolidge that he granted the “Wonder-Boy’s” request to let his mother and sisters emigrate to America.

Seymour Rexite, c 1940.

Seymour Rexite often sported evening dress for his uptown society gigs.

An important Yiddish singer and performer in her own right, Miriam Kressyn translated American standards into Yiddish for her husband, Seymour Rexite.

Seymour Rexite is pictured here in his apartment in lower Manhattan. Next to him is the Wollensak reel-to-reel tape player he used to listen to his old broadcasts.

This documentary comes from Sound Portraits Productions, a mission-driven independent production company that was created by Dave Isay in 1994. Sound Portraits was the predecessor to StoryCorps and was dedicated to telling stories that brought neglected American voices to a national audience.

The Jewish Philosopher

C. Israel Lutsky, the Jewish Philosopher

Before Dr. Laura, before Dr. Ruth, there was C. Israel Lutsky, the Jewish Philosopher. From 1931 to the mid-’60s, Lutsky took to the air daily with letters from listeners seeking advice. He replied with spoonfuls of folk wisdom and dollops of abuse.

Charlatan or sage, Lutsky was one of the most beloved and listened-to figures from the golden age of Yiddish radio. No other radio personality delved so deeply into the personal lives of his listeners. From men lamenting overextended family business to women bemoaning no-good children, Yiddish-speakers of all stripes solicited Lutsky’s counsel on issues too sensitive for the ears of friends and relatives. His pronouncements on their fate veered in tenor from the singsong melody of Torah study to the gravity of an Old Testament patriarch in no way averse to sputtering rage. That the letters he expounded upon were written by his copywriter never diluted the strength of his convictions, or his determination to see his advice followed to a T.

Short, pugnacious, and dapper to the point of risibility, the cigar-chomping Lutsky was an entertainer above all else. The “C” in his name stood for cantor, a role in which he had early success before going on to become an amateur pugilist, a vaudevillian, a socialist organizer, a cub reporter, and ultimately a radio personality. In this long-lived function he demonstrated a hypnotist’s talent in bringing his correspondents to life in listeners’ minds, turning private grief into public catharsis and transforming platitudes into pearls of wisdom.

In short, the Jewish Philosopher was a snake-oil salesman, and as such knew it wasn’t enough to gather a crowd. He needed to sell, sell, sell — and he did it with cantorial fervor. His longtime sponsor, Carnation Milk, was so pleased with his impassioned promotions they awarded him a pension at his retirement.

But shilling for sponsors was only the tip of the iceberg. Lutsky launched the Philosopher’s League, a kind of lonely heart’s club devoted to spreading his teachings. And he went multimedia, publishing a magazine dedicated to himself.

Though famously attached to Carnation Milk, his decades-long sponsor, C. Israel Lutsky plugged for a variety of companies, including Chicken of the Sea Tuna and St. Joseph’s pharmaceuticals. The above promotional poster dates from the 1930s. The Yiddish tag line runs: “The Jewish Philosopher: He knows, he sees, he helps, he consoles.”

In 1937, Lutsky founded a magazine dedicated to himself. An outgrowth of the Philosopher’s League, a lonely hearts club which bore Lutsky’s invaluable imprimatur, the magazine appears to have met with little success. Only one issue was published.

Dick Sugar, the narrator of the Yiddish Radio Project documentary about C. Israel Lutksy, was the Philosopher’s English language announcer from 1946-1957.

Carl Reiner, legendary actor, writer and producer, is the voice of the Jewish Philosopher in the Yiddish Radio Project documentary about C. Israel Lutksy.

Isaiah Sheffer, creator of Selected Shorts and artistic director of Symphony Space, was once the Philosopher’s English-language announcer.

The Philosopher’s Magazine and League

In 1937, in a bid to capitalize on the success of his radio show and his growing stature among listeners, C. Israel Lutsky launched the Jewish Philosopher’s League, Incorporated, “an organization that is truly a Cultural and Spiritual Cult,” and The Jewish Philosopher magazine, its house organ. Promising “a successful challenge to loneliness of the heart … loneliness of the soul … loneliness of the spirit,” the league was in essence a matchmaking service built around the magnetic personality of its leader.

Having paid the $10 initiation fee and $5 annual dues, league members could attend sponsored activities like dances, amateur drama classes, and boat rides. If the balance sheet totted up positive for Lutsky, no tally exists on aching hearts salved by the venture. Evidence does however exist that at least one heart was broken: by the Jewish Philosopher’s League treasurer, Morris Shimshak (see photo). (A little while later, Shimshak found himself on the outs, following a squabble with Lutsky about matters financial.)

Endorsements of the league were dutifully penned into every Jewish Philosopher article, written by members of the league’s executive committee. True to its mission, The Jewish Philosopher ran a biographical sketch of Lutsky, an open letter from Lutsky to his listeners, and a novelette based on the solution of a letter writer’s woes. The first issue, dated November 1937, was also the last.

Jack Luth (né Lutsky) was C. Israel’s brother and the President of the Philosopher’s League, Inc.

Jack Luth (né Lutsky) was C. Israel’s brother and the President of the Philosopher’s League, Inc.

Solomon Dickstein was the Philosopher League’s second vice-president and one of Lutsky’s most loyal friends.

Morris Shimshak, the League’s treasurer, and Lutsky were eventually to have a falling out over an unsuccessful investment scheme.

This Philosopher’s League membership card belonged to Morris Shimshak, the League’s treasurer.

A Lutsky letter suggesting controversy in the League.

Rae M.K., who professed her unrequited love for Morris Shimshak by letter.

Lutsky on Carnation Milk

Day in, day out, for three decades running, Lutsky began his program with a freshly written tribute to the wonders of Carnation Milk. He lauded the economic efficiency of Carnation’s plants, the mysterious nutritional benefits of its powdered milk crystals, the allergy-preventing properties of its canned milk — all with the same emotion and sense of purpose that went into responding to “listener” letters. The force of Lutsky’s devotion was in full evidence when he summarily fired Isaiah Sheffer, his English-language announcer, for garbling a Carnation ad.

Lutsky was so enamored of his patron that he always sported a white Carnation in his lapel and, for his vacations, toured Carnation plants across the country, prancing about like Napoleon at Austerlitz. It thus seems apt that one-third of the surviving recordings of the program feature Lutsky dispensing Carnation ads rather than the milk of human kindness.

This documentary comes from Sound Portraits Productions, a mission-driven independent production company that was created by Dave Isay in 1994. Sound Portraits was the predecessor to StoryCorps and was dedicated to telling stories that brought neglected American voices to a national audience.

Levine and His Flying Machine

Introduction

Everyone has heard of Charles A. Lindbergh, the first man to fly the Atlantic. But does the name Charles A. Levine ring a bell? Likely not. Yet seventy-five summers ago the two men were locked in a battle for aviation history — one as a pilot, the other as a promoter.

Levine, a 30-year-old millionaire who had made his money buying and selling World War One surplus materiel, had entered the competition for a $25,000 prize for the first person to complete a nonstop flight from New York to Paris. Lindbergh beat him to it on May 20, 1927, but the following day the young entrepreneur announced that his privately owned airplane would presently fly farther faster — and with a “mystery passenger” aboard. The pilot, he stated, would be one Clarence Chamberlin. The mystery passenger remained a mystery.

On June 4, 1927, thousands gathered at Roosevelt Field on Long Island, New York, to witness the takeoff. While they waited, Charles A. Levine climbed into the back of his plane and had Chamberlin taxi him around the airfield. No one thought much of it until the plane was halfway down the runway and gaining speed.

Suddenly it was clear: The mystery passenger was none other than Levine himself. The millionaire’s wife fainted. His children wept. The press had a field day.

Forty-two hours later, Levine and Chamberlin ran out of gas and landed safely in a peasant’s wheat field in central Germany. Despite being 40 miles short of the intended destination of Berlin, Chamberlin had smashed Lindbergh’s distance and speed record. And Levine had become the world’s first transatlantic air passenger — as well as an international hero whose face was plastered across newspapers from Europe to America.

The euphoria was greatest among American Jews, for whom Levine was a new symbol of Jewish courage and fortitude. Yiddish radio stations and newspapers covered and re-covered the story and Jewish musicians wrote songs about him.

It seemed Levine had made history.

Ardith Polley is the daughter of Charles A. Levine and the co-narrator of the Yiddish Radio Project documentary about his life.

Charles A. Levine (right) and his pilot Clarence Chamberlin (left) pose for a picture a few days before their historic flight across the Atlantic.

The Columbia prior to its transatlantic flight.

A crowd gathered at Roosevelt Field to witness the historic flight.

Levine’s wife and children tune in to the radio for the latest news on Levine’s flight. The toddler is Ardith.

Upon arriving in Berlin, Levine (left) and Chamberlin (right) receive heroes’ welcomes.

When Mrs. Levine saw this published photo of her husband amidst two young Frauleins, she immediately packed her bags for Europe.

Following their meeting with President Von Hindenberg, Levine and Chamberlin leave the German President’s Palace accompanied by Ambassador Schurman. Later that summer, Levine would also meet Benito Mussolini.

Levine (center), with Chamberlin (left) and Maurice Drouhin (right). Later in the summer of 1927, Levine hired Drouhin to fly him back from Europe to the US. When the flight was cancelled, Levine flew solo from France to London to avoid paying Drouhin his $4,000 forfeit fee.

Levine stands with his mistress Mabel Bolls, aka “The Queen of Diamonds.” Levine’s public affair caused his wife to seek a divorce. “After that,” recalls Levine’s daughter, “he was like Napoleon without his Josephine.”

The Songs

In the weeks following Levine’s triumph, the Jewish-American community was in a state of rapture as across the sea one of its own was received by European dignitaries from Hindenburg to Mussolini. On Manhattan’s Lower East Side, the Jews spoke of little else.

“The anti-Semites in Germany and the anti-Semites around the world will have to take their hats off to Levine the Jew,” pronounced the New York Yiddish daily newspaper Der Tog. “No longer will we be obliged to prove that Jews are as capable and strong on the field of physical bravery as on the field of intellectual achievements.”

Within a month a half-dozen songs had been written in Levine’s honor. The transatlantic flyer was seen as heralding the advent of the modern Jewish hero: independent, courageous, and proud. Two of the songs made musical allusion to “Ha’Tikvah” (The Hope), the then unofficial Jewish national anthem. The implication was unmistakable: here was a defining character for Jewish aspiration.

A Hero Is Forgotten

On February 28, 1937, a short article titled “Headliner Fades Out” ran in the back pages of the Los Angeles Times. A sort of living obituary, the piece chronicled the precipitous fall of an ephemeral modern legend.

Since the summer of 1927, everything Charles A. Levine had touched ended in ruin. In 10 years he had lost everything: fortune, family, and fame — the latter returning momentarily in 1934, when, the LA Times article reports, he was “found unconscious in the kitchen of a friend’s home, with five gas jets on.” In the eyes of the writer summarizing his life, Levine had sunk plenty low. In fact, he had a ways to go.

A few months following the article’s appearance, the erstwhile headliner was back in the news, this time in connection with a Federal charge of tungsten smuggling. After spending 18 months in jail, Levine was eventually busted again, this time for the smuggling of an illegal alien. (The “alien” was a German Jew denied an American visa in his attempt to escape Hitler.)

The former hero’s indignities were for a time thought amusing enough for newspaper back pages, but eventually even the tabloids lost interest. By the 1950s only the FBI cared to investigate further.

Hunted by the FBI

Fifteen years after his tungsten smuggling conviction, Levine still owed the lion’s share of his $5,000 fine. In 1952 the Justice Department sought to ascertain whether the cash was recoupable.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation operative assigned to the case picked up Levine’s scent in the shadowy world of New York rooming houses and dubious businesses. But laying hands on the former flier proved far more difficult. Levine had become a ghost, resurfacing sporadically among acquaintances to make a pitch or borrow a few bucks and then disappearing for days, weeks, or years at a time.

No one, not even Levine’s daughter, knew where he lived or how he survived. Those who saw him remarked on the shabbiness of his suit and his evident lack of money. There was hardly a soul to whom he didn’t owe money. According to his notes, the FBI agent had trouble believing that Levine “was at one time a prominent newsworthy individual.”

After evading the FBI for 26 months Levine was finally discovered in April 1956, thanks to a tip from a former business associate seeking revenge for an unpaid loan. But the task of catching Levine was still easier than getting him to cough up, and in 1958 the FBI closed the case without recovering a penny.

Although the FBI ultimately failed in its mission, the paper trail it left behind illuminates an otherwise obscure chapter in Levine’s drawn out fall.

Having finally hit rock bottom, Charles A. Levine stayed there for the remaining days of his life. He breathed his last on Dec. 6, 1991, cared for by an older woman who had picked him up off the street some 30 years earlier, having vaguely remembered his name from headlines of yore.

In 1953, Levine becomes the focus of an FBI investigation. Levine had avoided paying the fine from his 1937 smuggling conviction, and now the Feds want to collect. Levine’s case is reopened and an agent is assigned to tracking down the evasive former flyer.

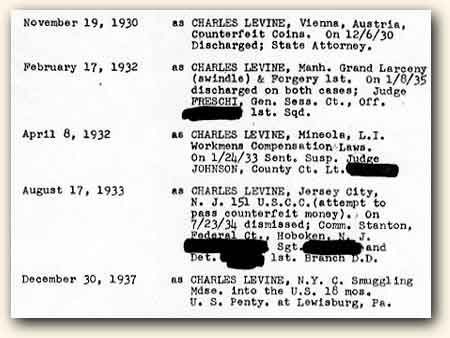

In the course of his investigation, the agent discovers Levine’s rap sheet.

The agent questions several of Levine’s former acquaintances. He learns that Levine has hit on hard times but finds few clues to Levine’s whereabouts.

A clerk at a seedy New York City hotel confirms that Levine is living there. The agent is instructed by his superiors not to contact Levine, for fear that Levine may leave town if apprised of the investigation.

Sure enough, when Levine learns that the FBI is pursuing him, he leaves the hotel. He apparently spends the next year moving among several rooming houses. He is occasionally seen at a salesmen’s office in New York City, where he collects his mail.

The FBI agent is put in touch with Levine’s brother. The brother says that he, too, is owed money by Levine, who has been avoiding him for some time.

A recent employer of Levine agrees to assist in the investigation, having been stiffed by Levine for thousands of dollars worth of company equipment.

Acting on a tip from a former associate, the agent finally locates Levine in 1956 and calls him in for questioning.

When called in by FBI officials for a second round of questioning, Levine refers to the Statute of Limitations on the collection of his fine.

In 1958 Federal officials declare Levine’s debt uncollectible and close his case…

…only to re-open it nine years later, stating that the case had been closed “in error.” The last record of the case is dated June, 1967. Though Levine again pleads protection under the Statute of Limitations, Federal authorities continue to believe that the claim “may be collectible.”

In the meantime, Levine has come to the attention of the FBI in an unrelated matter. Files dating from 1962 allege that Levine has been involved in the illegal sale of electronic equipment to the Government of Venezuela. The investigation is closed the following year due to a heavy caseload in the New York Customs Department.

Read Levine’s complete FBI file here.

This documentary comes from Sound Portraits Productions, a mission-driven independent production company that was created by Dave Isay in 1994. Sound Portraits was the predecessor to StoryCorps and was dedicated to telling stories that brought neglected American voices to a national audience.

Commercials on Yiddish Radio

Introduction

On radio stations that carried Yiddish-language broadcasts in the 1930s and ’40s, an inordinate amount of airtime was devoted to advertising. At the height of its popularity WEVD landed accounts from brand-name sponsors like Manischewitz, Hebrew National, and Campbell’s Soup. But smaller stations like Brooklyn’s WLTH and WBBC were perpetually having to go into the community to rustle up business from mom-and-pop stores on the Lower East Side and along Pitkin Avenue in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn.

Much to their listeners’ dismay, these stations often filled as much as 50 percent of the broadcast day with pitches. Often inspired, occasionally insipid, commercials from neighborhood stores were the lifeblood of Yiddish radio.

To the ethnographer, these shards provide a vivid snapshot of what ordinary people wore, ate, drank, and cleaned their houses with. For the rest of us, they’re simply some of the most memorable ads ever created — from the Joe and Paul clothiers jingle to the language-murdering ad copy of Mitchell Levitsky, WEVD’s advertising king.

Chunky Chocolate, which was located on Ridge Street on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, was among Yiddish radio’s most loyal sponsors.

Mitchell Levitsky, WEVD’s advertising king, working the phones, c1940. His accounts included Chunky Chocolate, Portnoy’s Trusses, and Mrs. Weinberg’s Kosher Chopped Liver.

Mitchell Levitsky: The Advertising King

Few figures from the golden age of Yiddish radio are more widely if anonymously recalled than Mitchell Levitsky. He began his radio career in 1927, at age 18, as a Yiddish announcer for New York’s WFAB. But by the time he arrived at WEVD in 1943, he had discovered his true calling: selling radio ads.

As the patriarch of advertising sales reps, Levitsky proved an unstoppable force on the streets of the Lower East Side, tossing shop after shop into his game sack. Dick Sugar, the veteran WEVD announcer, recalls that shop owners along Second Avenue would push Levitsky out the front door only to turn around and see him coming through the back. Yet one way or another, Levitsky always got his man. Portnoy’s Trusses, Mrs. Weinberg’s Frozen Kosher Chopped Liver, Meyer Mehadrin Kosher Herring Products — one and all fell before Levitsky’s relentless onslaught.

Shopkeeper’s buying ads from Levitsky hired not just WEVD airtime but the on-air talents of the advertising king, whose delivery was legendary among Jewish New Yorkers. When Levitsky spoke English it sounded like Yiddish was his first language, and when he spoke Yiddish you would swear he was born here. He wended his way through ad copy as though navigating a minefield, stopping to rest on “ums” and “ahs” and regrouping during significant pauses that lapsed into dead air. Yet despite such caution, WEVD listeners heard pitches for bedroom “suits” and hotel rooms with “wall-to-wall telephones in every room.”

Levitsky wooed advertisers by impressing upon them that one little commercial would make them big-time theatrical producers. Each pint-size patron of the arts also got an annual cruise of the East River complete with an open bar and celebrity shipmates like Jewish boxing great Benny Leonard. By the by, Levitsky would corner his guests to discuss a renewal of their contract.

In addition to hawking ads, Levitsky hosted knockoff shows like the advice program Jewish Court of Human Relations and a Sunday morning children’s hour. He was the announcer for The Chunky Program, featuring the Joseph Rumshinsky Orchestra. And he was the host of the long-running Oddities in the News, on which he read offbeat items gleaned from the week’s papers. Listeners to these programs recall no dearth of commercial messages.

Mitchell Levitsky, 1933.

Levitsky organized an annual East River cruise for his customers. Celebrities like Jewish boxing great Benny Leonard (center) were featured guests.

Revelers aboard Levitsky’s East River cruise enjoy a semi-private moment.

Levitsky (right) occasionally read ad copy on Rabbi Rubin’s (left) on-air court.

Inspired by Rabbi Rubin’s example, Levitsky created his own mediation program, which he called The Jewish Court of Human Relations.

“Joe and Paul”

Paul Kofsky opened his first clothing store in Brooklyn in 1912. He called it Joe and Paul – inventing an imaginary cohort, Joe, because he thought people would trust him more if they thought he had a partner. By the early ’30s, Kofsky, a dapper man with a penchant for paper neckties, held sway over a successful chain, with new locations in Manhattan and the Bronx. Sartorial success aside, Kofsky had a greater ambition: to rub shoulders with the Yiddish stars of the day.

He made his dream come true in 1936 by walking into WLTH’s studio and hiring the station’s musical director, Yiddish theater composer Sholom Secunda, to write a song advertising his store. As for the singing, Kofsky would handle that himself.

For the next decade, Kofsky spent most of his days shuttling between stations to perform his jingle live on the air and to talk theater shop with his fellow performers. The ad became more than ubiquitous; to many listeners, “Joe and Paul” was Yiddish radio.

So it happened that a young comedian named Aaron Chwatt (who later became Red Buttons) used “Joe and Paul” as the basis for an extended Borscht Belt parody of Yiddish radio. His routine centered on the fictitious station WBVD, whose programming consisted of commercials interrupted by more commercials, each sillier than the last. For listeners of Yiddish radio, the send-up hit home.

Called to service in World War Two, Red Buttons left the hugely successful skit in the Catskills, where the Barton Brothers comedy team picked it up from hotel staff who had learned it by heart. The Bartons recorded the bit in 1947 for the fledgling Apollo label and soon found themselves proud progenitors of the biggest Yiddish party record ever. According to Eddie Barton, three-quarters of a million records were sold in a span of a few months. The song was so popular it spawned a Latin cover arranged by Tito Puente.

Ironically, most people who bought the Barton Brothers’ 78 rpm never heard the original “Joe and Paul” jingle, which had always been confined to the range of New York City radio waves. Kofsky, it can be assumed, did not mind the additional exposure.

Joe and Paul clothiers was famous for its radio jingle, which was composed by Sholom Secunda, of “Bei Mir Bist Du Schoen” fame. The jingle was usually sung on-air by Joe Kofsky, the store’s owner, himself.

Joe and Paul’s Brooklyn store was located at 1586 Pitkin Avenue in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn.

Joe and Paul’s Manhattan store was located at the corner of Stanton and Delancey.

Red Buttons created a hit Borsht Belt parody of Yiddish radio based on the Joe and Paul jingle.

The Barton Brothers inherited Red Button’s “Joe and Paul” routine and turned into one of the best selling Jewish albums of all time.

“Joe and Paul” was such a hit that Tito Puente orchestrated a Latin style take-off of it for the Pupi Campo orchestra.

This photo of Eddie Barton was taken in Miami Beach, Florida, in April 2000. (The Yiddish Radio Project has since been unable to locate Eddie. If you know of his whereabouts, please e-mail us at [email protected]).

Selected Commercials

Campbell’s Soup

Miriam Kressyn, WEVD, circa 1950.

Hebrew National

WEVD, circa 1950.

Lifschitz Wine

WEVD, circa 1940.

Sterling Salt

WLTH, circa 1942.

This documentary comes from Sound Portraits Productions, a mission-driven independent production company that was created by Dave Isay in 1994. Sound Portraits was the predecessor to StoryCorps and was dedicated to telling stories that brought neglected American voices to a national audience.