The Ground We Lived On

The Ground We Lived On documents the loving relationship between journalist Adrian Nicole LeBlanc and her father, Adrian Leon LeBlanc, in the last months of his life. Using recordings she made of her father, namesake and inspiration from his hospital bed in the family living room, The Ground We Lived On is an ode to the ordinary ways we continue loving even as we are letting go.

In January 2003, Adrian Leon LeBlanc was 85 years old and the father of four. He was in the final stages of lung cancer and had just entered hospice care. He spent his days in his house in Leominster, Massachusetts, a working-class town near Boston, in the company of his family. During this time, Adrian Nicole LeBlanc regularly drove in from her home in New York City to visit her father.

Each time she visited, Adrian Nicole taped her conversations with her father. She wanted to preserve a record of their relationship and capture her father’s voice. Adrian Leon LeBlanc had been a labor activist and World War II veteran; as such, he had always been outspoken on behalf of others’ interests but was reluctant to talk about himself and his personal feelings. Still, he welcomed his daughter’s recorder, believing that documenting the last months of his life might help other families who were going through similar experiences.

The Ground We Lived On is a story of loving and losing a parent and the record of a father’s final gift to his daughter: helping her to conceive of a world without him.

Premiered November 13, 2006, on All Things Considered.

This documentary comes from Sound Portraits Productions, a mission-driven independent production company that was created by Dave Isay in 1994. Sound Portraits was the predecessor to StoryCorps and was dedicated to telling stories that brought neglected American voices to a national audience.

My Lobotomy

Introduction

On January 17, 1946 a psychiatrist named Walter J. Freeman launched a radical new era in the treatment of mental illness in this country. On that day he performed the first-ever transorbital or “ice pick” lobotomy in his Washington, D.C. office. His patient was a severely depressed housewife named Sallie Ellen Ionesco.

After rendering her unconscious through electroshock, Freeman inserted an ice pick above her eyeball, banged it through her eye socket into her brain, and then made cuts in her frontal lobes. When he was done, he sent her home in a taxi cab.

Freeman was convinced he’d found the answer to Sallie Ellen Ionesco’s depression. He believed that mental illness was related to overactive emotions, and that by cutting the brain he could cut away those feelings.

In the era before psychiatric drugs – when state institutions were over-flowing with mentally ill patients often living in snakepit conditions – hospitals, families, and the press were eager to embrace “miracle” cures like the “ice pick” lobotomy.

For over two decades, Freeman – equal parts physician and showman – became a barnstorming crusader for the procedure. He traveled in a van to 55 psychiatric hospitals across the country, performing and teaching the transorbital lobotomy.

Before his death in 1972, he’d crossed and re-crossed the nation 11 times, and had performed the “ice pick” lobotomy on no less than 2500 patients in 23 states.

Freeman operating at Western State Hospital, Washington State, in July 1949 / © Bettmann/CORBIS.

Sallie Ellen Ionesco, the first patient to receive a transorbital lobotomy from Dr. Freeman, Virginia, May 2004. / Harvey Wang.

Howard Dully

Howard Dully was one of the youngest patients to receive an “ice pick” lobotomy. Today, he is a tour bus driver living in California.

In collaboration with Sound Portraits producers Piya Kochhar and Dave Isay, Dully embarked on a remarkable two year journey to uncover the hidden story behind the lobotomy he received as a 12-year-old child.

While working on this documentary, Howard Dully traveled to Washington, D.C. to view his sealed patient records. Dr. Walter Freeman photographed each transorbital lobotomy procedure. Howard Dully is the first patient ever to obtain a picture of his own operation.

Dully’s personal journey to find out about his lobotomy took him around the country as he interviewed lobotomy patients, their family members, and people who witnessed the operation. “This is my odyssey,” said Dully. “Everyone has one thing have to do before they die, and this is mine.”

Warning: Some of following images are graphic.

A childhood photo of Howard Dully.

A photo of Dully’s stepmother, Lou.

|

|

|

||

Dully before, during, and after his “ice pick” lobotomy. / Walter Freeman, 1960

An excerpt from Dully’s medical records.

Dully in front of his childhood home in Los Altos, California, where he lived until age 12. / Harvey Wang

Walter Freeman’s son, Franklin Freeman, at his home in San Carlos, California. / Harvey Wang

Dully and Dr. Robert Lichtenstein, who was in the operating room during Dully’s lobotomy, at the doctor’s home in Los Altos, California. / Harvey Wang

Dr. Karl Pribram, Dr. Walter Freeman’s friend and colleague, at home in Washington, D.C. / Harvey Wang

Dully and his father, Rodney Dully, in San Jose, California. / Harvey Wang

Oral Histories

Helen Culmer

Helen Culmer is 76 years old and lives by herself in Point Pleasant, West Virginia (photo by Harvey Wang). In 1954 she was a nurse at an all-black hospital for the insane.

My name is Helen Culmer. I was a nurse at Laikin State hospital in West Virginia for 34 years. In 1954 I assisted Dr. Freeman in doing a transorbital lobotomy. I was a new nurse at the time and I was drafted to work in there with him. Had no idea about what I was getting into. But I was curious and I wanted to see it. And I saw it…. Oh my, the room was full of people! Everybody wanted to see what’s going on, people from town and everywhere else come up to witness this occasion.

He came, and I held the patient’s head and he did the lobotomy. He had an instrument– to me it looked like a nail, a great big nail. It had a sharp point, and he inserted this in the corner of the individual’s eye and banged it with a mallet, I guess it was. And then he pulled from one side and pulled to the other side. It wasn’t easy… It wasn’t easy to watch… I know that day we lost one patient because they couldn’t stop the bleeding and I can’t remember if any others died…

It wasn’t… It wasn’t what I thought it might be. To me it was cruel. But that was my opinion. I was just doing the job I was employed to do. Remember I’ve seen all kinds of things in my line of work–so if I stopped and dwelled on each little thing, I’d be hurting.

Wolfhard Baumgartel

Wolfhard Baumgartel lives in Albany, Ohio (photo by Harvey Wang).

I am Wolfhard Baumgartel. I’m 82 years old. I was a staff physician at the Athens State Hospital in Ohio in 1954. Not long after I started at the hospital, I had the opportunity to watch Dr. Walter Freeman perform a series of transorbital lobotomies. I was neither a psychiatrist nor a neurologist. I was just a very very green beginner here who hardly spoke any English, and he was a big shot at that time.

As far as I remember he probably did between 15 or 20 on that particular day. Doctor Freeman did not leave the operating room after each procedure – the patient went out, the next patient was ready to come in, had his procedure done, went out again, and then the next patient came in…

I remember that he was relaxed. He was very calm while he was operating. He made it look easy to do it. I think he had an extremely self-confident personality. He didn’t have any qualms. He wanted to prove that he was right, he was convinced that he was right. I thought, “How can a man be relaxed just going blindly into a brain?!” But of course, I didn’t have the authority to say, “Stop that!”

These patients were not young ones. I think they were all about 30 or 40 years old. I knew two of them. After the operation I found that they had changed in their personality. My impression, which I remember still, was that they didn’t ask any questions. Expression of deep turmoil in their heart or in their soul was subdued. There was something missing: emotions, I would say. You know, if you were to converse with somebody there’s always emotion with it. Just take all of your emotion out of a conversation with somebody and what’s left?

Patricia and Glen Moen

Patricia Moen was lobotomized by Walter Freeman in 1962 at the age of 36. This is the first time she and her husband have spoken about her lobotomy (photo by Harvey Wang).

GLEN MOEN: My name is Glen Moen. I am 79 years old. I signed the release for Pat’s lobotomy.

PATRICIA MOEN: We have not talked about it, since I had the lobotomy – I don’t think ever. My husband is not a great communicator.

GM: I don’t talk to her anymore than I have to.

PM: Glen – be nice! (both laugh). We’d been married about 13 years, and it just started. I cried all the time. I just was mentally no good.

GM: One night I came home and she said, “Well, I’ve done it now!” She’d taken a whole bottle of some kind of pills….

PM: That’s when the doctor decided it was time.

GM: He told me this was the last resort. I didn’t know what else to do.

PM: Dr. Freeman said you can come out of this a vegetable, or you can come out dead. And I guess I was miserable enough that I didn’t care.

GM: I was kind of worried because of the operation of severing a nerve in the brain…It sounded kind of wild to me!

PM: …He was afraid he was going to lose his cook.

GM: And I don’t like to cook.

PM: I remember nothing after I saw Dr. Freeman. I don’t remember going into the hospital, or having it done, or how long I was there. That’s all gone.

GM: We were coming back from San Jose after the operation, and Pat informed me that she couldn’t wait to get home because she wanted to file for divorce.

PM: Hmmmm…. Don’t remember that at all. I don’t think I said it.

GM: I think I just went on driving and ignored the situation and began to wonder to myself how much good did this operation accomplish. Really, I can see no changes in most areas except she is much easier to get along with.

PM: You didn’t see any change in the way I kept house? Or the way I—

GM: Nn… no…

PM: I was a more free person after I’d had it. Just not to be so concerned about things…. I just, I went home and started living. I guess is the best way I can say— I was able to get back into taking care of things and cooking and shopping and that kind of thing…

GM: Delighted at the way it turned out. It’s been a good life.

PM: Well, thank you.

More Information on Transorbital Lobotomy

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between a prefrontal lobotomy and a transorbital lobotomy?

The two procedures differ in how the doctor gets access to the brain. In a prefrontal lobotomy, the doctor drills holes in the side or on top of the patient’s skull to get to the frontal lobes. In the transorbital lobotomy, the doctor accesses the brain through the eye sockets. Freeman started out by doing prefrontal lobotomies, but later created the transorbital lobotomy, which he considered to be an improved version of the original procedure. The transorbital lobotomy left no scars (apart from two black eyes), took less than 10 minutes, and could be performed outside of an operating room. According to Freeman, it produced better results.

What effect did the transorbital lobotomy have on patients?

Freeman believed that cutting certain nerves in the brain could eliminate excess emotion and stabilize one’s personality. Indeed, many people who received the transorbital lobotomy seemed to lose their ability to feel intense emotions, appearing childlike and less prone to worry. But the results were variable, according to Dr. Elliot Valenstein, a neurologist who wrote a book about the history of lobotomies: “Some patients seemed to improve, some became ‘vegetables,’ some appeared unchanged and others died.” In Ken Kesey’s novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Randall McMurphy receives a transorbital lobotomy.

What type of patients received lobotomies?

Freeman’s most common rationale for performing lobotomies was to treat schizophrenia, especially in patients who’d just recently been diagnosed with the disease. He also used the procedure to treat chronic pain and suicidal depression. A New York Times article from 1937 stated that people with the following symptoms would benefit from a lobotomy: “Tension, apprehension, anxiety, depression, insomnia, suicidal ideas, delusions, hallucinations, crying spells, melancholia, obsessions, panic states, disorientation, psychalgesia (pains of psychic origin), nervous indigestion and hysterical paralysis.”

How many people were lobotomized in the United States?

About 50,000 people received lobotomies in the United States, most of them between 1949 and 1952. About 10,000 of these procedures were transorbital lobotomies. The rest were mostly prefrontal lobotomies. Walter Freeman performed about 3,500 lobotomies during his career, of which 2,500 were his “ice pick” procedure.

Did Freeman operate on Rosemary Kennedy?

Yes, he did in the summer of 1941. This operation was one of his most famous failures. Freeman and his neurosurgeon partner James Watts performed a prefrontal lobotomy on Rosemary Kennedy, leaving her inert and unable to speak more than a few words. After her lobotomy she was sent to live at Saint Coletta’s School in Wisconsin, where she remained until her death in 2005 at the age of 86.

Did Freeman operate on the actress Frances Farmer?

There’s some controversy about this. Though Freeman’s son Frank Freeman believes that his father did, there is no documentary evidence to support this. To learn more, visit Shedding Light on Shadowland.

Lobotomy Timeline

November 14, 1895:

Walter Jackson Freeman II born.

1924:

Freeman arrives in Washington, D.C. to direct labs at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital.

November 12, 1935:

Neurologist Egas Moniz performs first brain surgery to treat mental illness in Portugal. He calls the procedure a “leucotomy.”

September 14, 1936:

Freeman modifies Moniz’s procedure, renames it the “lobotomy,” and with his neurosurgeon partner James Watts performs the first ever prefrontal lobotomy in the United States. His patient is Alice Hood Hammatt, a housewife from Topeka, Kansas.

1939:

While working in his office, Egas Moniz is shot multiple times by a patient. He survives but is left partly paralyzed.

1945:

Freeman begins experimenting with a new way of doing the lobotomy, after hearing about a doctor in Italy who accessed the brain through the eye-sockets.

January 17, 1946:

Walter Freeman performs the first transorbital lobotomy in the United States on a 29-year-old housewife named Sallie Ellen Ionesco in his Washington, D.C. office.

1949:

Egas Moniz wins the Nobel Prize for lobotomy. He’s nominated by Walter Freeman.

1950:

Watts expresses disapproval of the transorbital lobotomy procedure, and the two eventually break their long-time partnership. Freeman barnstorms the nation, performing and teaching the transorbital lobotomy at state hospitals.

July 1952:

Freeman performs 228 transorbital lobotomies in a two-week period in West Virginia for a state-sponsored lobotomy project, dubbed “Operation Ice Pick” by newspapers.

1954:

Era of widespread hospital psychosurgery fades away with introduction of chlorpromazine (Thorazine). Freeman moves to California and sets up an office in Sunnyvale.

1955:

Egas Moniz dies at the age of 81.

December 16, 1960:

Freeman lobotomizes Howard Dully, 12, at Doctor’s General Hospital in San Jose, California.

February 1967:

Freeman performs his final transorbital lobotomy on Helen Mortensen. It’s her third lobotomy by him. She dies from a brain hemorrhage following the procedure. Freeman is banned from operating again.

1968:

Freeman retires and embarks on cross-country follow-up studies of his lobotomy patients.

May 31, 1972:

Freeman dies of cancer at age 76.

Additional Resources

- Last Resort: Psychosurgery and the Limits of Medicine, by Jack Pressman

- Great and Desperate Cures: The Rise and Decline of Psychosurgery and Other Radical Treatments for Mental Illness, by Elliot S. Valenstein

- The Lobotomist: A Maverick Medical Genius and His Tragic Quest to Rid the World of Mental Illness, by Jack El-Hai

- A Hole in One (2004), a film about the “ice pick” lobotomy starring Michelle Williams and Meatloaf.

An excerpt from Dr. Walter Freeman’s unpublished autobiography.

The Christmas card Dr. Freeman sent to his lobotomy patients.

Producers’ Notes

“My Lobotomy” is Howard Dully’s deeply personal journey to uncover the secrets of his past. Like many Sound Portraits documentaries, “My Lobotomy” is told from the point of view of the subject. In this case, the narrator is Howard Dully, a 56 year old bus driver who received a lobotomy when he was 12. As producers, our job entailed verifying the historical and factual accuracy of the documentary, while at the same time enabling Howard to share his experience in his own words.

During the two years we spent working on this documentary, we conducted dozens of in-person and telephone interviews. By the end we had recorded nearly 100 hours of tape. Distilling all of this into a 22 minute radio documentary (the longest segment possible for broadcast on All Things Considered) was a challenging task. The guiding principle behind all of our editorial decisions was to uphold the essential truth and integrity of Howard’s story.

We’d like to share with you the thinking behind a few of those decisions:

- Howard’s Medical Records

- Rebecca Welch/Anita Johnson McGee

- Portrayal of Walter Freeman

- Interviews not included in “My Lobotomy”

Medical Records

There were several allegations in Howard Dully’s medical records that we did not address in the documentary because of time limitations and because experts and witnesses we interviewed determined that they were unfounded and inaccurate. However, there are two issues we feel it is important to address here:

- According to his medical records, Dr. Freeman diagnosed Howard as schizophrenic. Independent analysis of his records indicate that this was an unfounded and incorrect diagnosis.

- In a medical paper published after Howard’s operation, Dr. Freeman wrote that he’d operated on a 12-year-old patient (identified as “H.D.”) because the patient had severely injured his infant brother. This allegation is incorrect; Howard never severely injured his younger brother. Moreover, Dr. Freeman learned about this alleged assault after he had already decided to perform a lobotomy. (According to his records, Dr. Freeman recommended the procedure on November 30, 1960, then heard about the alleged assault on December 7, 1960. Howard’s stepmother told Dr. Freeman that Howard had attacked his infant brother, but our interviews with other family members, including his father, revealed that this incident never occurred.)

Rebecca Welch/ Anita Johnson McGee

Rebecca Welch’s mother, Anita Johnson McGee, was Walter Freeman’s patient. She received three lobotomies. Freeman performed the first one; the other two lobotomies were performed by doctors he recommended. While it’s impossible to pinpoint exactly what caused her current condition (whether it was her three lobotomies or years of electroshock treatment and drugs), her daughter holds Walter Freeman responsible. After speaking with Rebecca Welch, reading her mother’s medical records, and interviewing other family members of lobotomy patients, we felt her story expressed a common sentiment. We believe it was important to include it in the documentary.

Portrayal of Walter Freeman

Opinions on Walter Freeman vary enormously. In “My Lobotomy” we portrayed Walter Freeman through Howard Dully’s eyes after considering all of the evidence we together uncovered. By the end, we saw him as a physician who started out with good intentions, but whose ego and hubris caused him to lose direction. This opinion was verified by numerous other sources.

Interviews Not Included in “My Lobotomy”

Distilling 22 minutes from nearly 100 hours of tape meant that we couldn’t include everyone we interviewed. Below is a list of all the interviews we conducted. Even though some were not included in “My Lobotomy,” they were all essential to the shaping of the final documentary.

Recorded Interviews:

- Patricia Derian: witnessed Walter Freeman operating when she was a student nurse in 1948.

- Dr. Karl Pribram: friend and colleague of Walter Freeman.

- Helen Culmer: a nurse at Laikin State Hospital in West Virginia. Read her oral history above.

- Dr. Wolhard Baumgartel: a doctor at Athens State Hospital in Ohio. Read his oral history above.

- Larry: a psychiatric ward attendant at Herrick Memorial Hospital in Berkeley, CA in the 1960s, who requested that his last name not be used.

- Dr. Paul Chodoff: one of Walter Freeman’s four student interns in 1946. He is a psychologist.

- Ann Krubsack: was lobotomized by Walter Freeman in January, 1961 at Doctor’s General Hospital in San Jose, California.

- Dr. Paul Freeman: one of Walter Freeman’s three sons. He is a psychologist.

- Dr. Walter Freeman III: a professor of neurobiology at the University of California. Frank Freeman’s twin brother.

- Patricia and Glen Moen: she was lobotomized, and her husband, Glen, signed the release. Read their oral history above.

- Barbara Dully: Howard Dully’s wife.

- Kathleen: a relative of one of Walter Freeman’s lobotomy patients, who requested her full name not be used.

- Dr. Gary Cordingley: neurologist at Athens State Hospital.

- Dr. Robert Lichtenstein: nerologist who was in the operating room during Howard’s “ice pick” lobotomy.

Interviewed by Phone:

- Joel Braslow: author, “Mental Ills, Bodily Cures-Psychiatric Treatment in the First Half of the Twentieth Century,” University of California Press, 1997.

- Robert Whitaker: author, “Mad In America-Bad Science, Bad Medicine, and the Enduring Mistreatment of the Mentally Ill,” Perseus Publishing, 2002.

- Edward M. Opton: author, “The Mind Manipulators: a non-fiction account,” Paddigton Press, 1978.

- Donald Diefenbach: author, professor of media studies, University of North Carolina: “Portrayal of Lobotomy in the Popular Press: 1935-1960.”

- Dr. Gerald Grob: author, “The Transformation of Mental Health Policy in Twentieth-Century America.”

- Vanessa Jackson: author, “In Our Own Voices: African American Stories of Oppression, Survival and Recovery in the Mental Health System.”

- Christine Johnson: founder of www.psychosurgery.org.

- Richard Ledes: director/writer of “A Hole In One.”

- Dr. Allan F. Mirsky: research psychologist at National Institute of Mental Health 1954-1961. Former president of International Nueropsychological Society.

- Dr. Maressa Orzack: worked with Dr. Mirsky on a study commissioned by Congress in 1976 on the affects of psychosurgery.

- Dr. Janet Colaizzi: author, “Predicting Dangerousness: Psychiatric Ideas in the United States, 1800-1983,” Ohio State University, 1983.

- Shirley Smoyak: president of The Journal of Psychiatric Nurses Association.

- Grayce Sills: Head of nursing at Ohio State hospital in the 1950s.

- Meredith Fulton: daughter of Jonathan Williams, who was Freeman’s partner after James Watts.

- Ann Dillard & E.N. Jr Dillard: daughter & husband of one of Freeman’s patients.

- W.K.: one of Freeman’s patients who shared his story off-the-record.

- C.B.: wife of one of Freeman’s patients who shared her husband’s story off-the-record.

Recorded in New York City. Premiered November 16, 2005, on All Things Considered.

This documentary comes from Sound Portraits Productions, a mission-driven independent production company that was created by Dave Isay in 1994. Sound Portraits was the predecessor to StoryCorps and was dedicated to telling stories that brought neglected American voices to a national audience.

Kaleria Palchikoff Drago, Witness to the Atom Bomb

On August 6, 1945, the United States dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, resulting in over 100,000 Japanese casualties. Shortly thereafter, the United States Strategic Bombing Survey sent members of its Morale Division to conduct a series of man-on-the-street interviews across Japan. Their recordings, 366 in total, have been housed in relative obscurity at the National Archives for the past 50 years.

This interview, recorded in December 1945, was the only English-language eyewitness account. The speaker, Kaleria Palchikoff Drago, was a 23-year-old Russian immigrant, whose parents had moved to Japan twenty-four years earlier. She had been living just outside of the city on the day of the bombing.

Recorded in Tokyo, Japan. Premiered August 5, 2005, on All Things Considered.

Kaleria Palchikoff Drago Oral History

Sergei Palchikoff, Kaleria’s father

My father and mother were anti-communists, so we left Russia to run away. The Bolsheviks were right behind us, trying to kill us all. My father, he commandeered a Japanese ship, and he told the captain, Take us.’ And so we all went to Japan sometime in 1921. I was three months old.

It was lovely. My two brothers were born there. We lived on Nagarekawa Street, right in the center of Hiroshima. There was a pond all around the house with beautiful Koi fish in it. It was very comfortable living.

My father, Sergei, was a music teacher for an American mission school. He played seven or eight instruments and taught the violin and cello. The whole of Japan was enjoying his music. He was also an instructor in the Military Academy of Japan.

As soon as the war began my dad got interned and considered a spy, although the military academy fought and said he’s not. After a year, he was released, but we were told by the military police to move to Ushita, in the suburbs of Hiroshima. It was about two and a half kilometers from the city. They thought we would be safer there because of the war. See, the Japanese people always felt some kind of responsibility for the white people. Always, always they regarded the white people as guests in their country, and they made us just as comfortable as they could.

Nikolai Palchikoff, Kaleria’s brother

My brother, Nikolai, had gone to America to study and continue his schooling when he was sixteen. Over there, the military grabbed him and he was sent to the Philippines. Right after the bomb was dropped, he was one of the first American soldiers to set foot in Hiroshima. He got permission to come to the city, where he was born and raised, to look for us. He thought that we had all perished. So he came, and he inspected the place where he was born and the house that stood there. He saw his bed mangled and all the stuff burned.

At the same time that day, dad happened to be down there to look for his colleagues, or to try to find some help in some way. He had to be careful and get out of there real quick. They said the radiation would get him if he stayed for more than two hours. Anyway, so my brother was in the jeep with some of his friends, and he saw my father. He went quickly towards my dad, and the jeep stopped in front of my dad, and my dad was just absolutely startled. Both sides thought that the other side was a vision.

Then my brother put him in the jeep and drove down to meet the family. We were all alive, so that was a great joy. My brother told us not to worry, he’d take care of everything. He arranged for my dad to work for the Americans at the Enlisted Men’s Club as a manager. He got me a job at General MacArthur’s headquarters in Tokyo. I was a secretary. It was my first job. That’s where the United States Strategic Survey interviewed me. And within a few years I was in the United States.

This documentary comes from Sound Portraits Productions, a mission-driven independent production company that was created by Dave Isay in 1994. Sound Portraits was the predecessor to StoryCorps and was dedicated to telling stories that brought neglected American voices to a national audience.

Jack Aeby, Atom-Bomb Photographer

On the morning of July 16, 1945, a young man named Jack Aeby snapped one of history’s most important and famous photographs: the only color picture of the first test of the atom bomb. Aeby was a 21-year-old amateur photographer. He was working as a technician on the Manhattan Project in Los Alamos, when he was granted permission to photograph a top-secret test, code named Trinity.

Recorded in Honolulu, HI. Premiered July 15, 2005, on All Things Considered.

Atomic History Timeline

September 1, 1939

Germany invades Poland: beginning of WWII.

September 23, 1942

The U.S. begins its effort to develop a nuclear weapon. This is code-named the “Manhattan Project,” and Colonel Leslie Groves is put in charge.

December 7, 1941

Japanese bomb Pearl Harbor.

December 8, 1941

U.S. enters WWII.

November 1942

Los Alamos, New Mexico selected as bomb development site, and J. Robert Oppenheimer is made director. Listen to newsreel [MP3, 506 KB].

May 5, 1943

Japan becomes the primary target for any future atomic bomb, according to the Military Policy Committee of the Manhattan Project.

May 8, 1945

Nazi Germany surrenders to the Allies.

July 16, 1945

The first atomic bomb is exploded at 5:29 AM Mountain War Time in the New Mexico desert. This is known as the “Trinity Test.” Listen to newsreel [MP3, 506 KB].

July 21, 1945

President Truman authorizes use of atomic bombs.

July 26, 1945

The U.S., Great Britain, and China issue the Potsdam Declaration, calling for the complete surrender of Japan. Listen to newsreel [MP3, 300 KB].

August 6, 1945

The atomic bomb, nicknamed “Little Boy,” is dropped on Hiroshima, Japan.

August 9, 1945

A second atomic bomb, nicknamed “Fat Man,” is dropped on Nagasaki, Japan.

August 14, 1945

Japan surrenders.

Information for time-line courtesy of the Los Alamos National Laboratory and the Los Alamos Historical Museum.

Trinity Scientists’ Oral Histories

Hans Bethe

Hans Bethe joined the team of scientists at Los Alamos in the summer of 1942. He was put in charge of organizing the theoretical division of the project. Mr. Bethe was a recent immigrant from Germany, whose family had escaped the Nazis.

We were terribly devoted to the project. We were convinced that it could be done. We had done lots of experiments in the experimental nuclear division showing that fission occurs immediately. We had done a lot of experiments on the implosion, which looked all right, but if it had not worked we would have tried again and we certainly would have kept at it, and we certainly would have dropped the bomb on Hiroshima.

I think everybody, after the test, felt he had made history and we were aware this would [be] world history from now on. We felt very accomplished. We felt we had done our job and we went on waiting for the actual drop on Japan.

I believed then and believe even more today, that the use of the atomic bomb, in that particular case was not only justified, but necessary. On the other hand ten years later it was totally different. Both the United States and the Soviet Union had hundreds, and then thousands of nuclear weapons, and so if a war had broken out between these two superpowers nuclear weapons would have been used from the beginning. They would not have been used to finish a war, but to start a war. And that makes all the difference.

Phillip Morrison

Scientists had been working at Los Alamos for over two years when Phillip Morrison arrived in August of 1944. Using models, he worked on measuring the reactivity of the bomb core. He rode in the car that carried the core of the bomb to the Trinity test site, and watched the explosion from Base Camp. After the bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Mr. Morrison traveled to Japan as a public relations liaison, and to measure the radioactivity on the ground.

It was a cool desert morning, the sun had not quite come up, the air was still, it had that curious chill of a hot place, which is the coolest hour of the day. And suddenly on that cold background the heat of the sun came to me before the sun rose. It was the heat of the bomb not the light but the heat was the first thing that I could feel: as though the sun had suddenly risen. But that was an unforgettable experience, because what you feel, I think, is deeper in the memory than what you just see. And so the notion that it was some way, in the most elementary human way, competitive with the full sun, that was the time I got the sense of the power of the bomb more than anything else. It was unforgettable.

I think it opened the door to a dreadful corridor down which we never finally went, despite being very close to it. I always felt one small nuclear war was all that anyone could tolerate. We can’t have a second one. I think the main thing I want to say is it has to stop, and its not stopping yet.

Edward Teller

Edward Teller, a European immigrant, arrived at Los Alamos in 1942. There, he worked on calculating the power of a nuclear fission reaction. Mr. Teller witnessed the Trinity explosion with a group of fellow scientists gathered ten miles from the test site.

For minus 30-seconds on we heard nothing. That was an eternity and I was sure that there has been a failure. Then there appeared a very small point of light, and my first impression was, I very distinctly remember, Is that all? I started to see the point rising and spreading [and] by that time I knew it was big. Then I was impressed. We knew that in a short time this would be used and it would be the real thing.

The bomb was dropped, and we saw the effects. I at once had a strong feeling of regret. Even today, I believe had we dropped the first bomb at an altitude of 30-thousand feet over Tokyo Bay that 10-million Japanese would have seen it and heard the thunderclash, including the emperor; probably it would have ended the war without a single person being hurt. And had that happened, we today would not be afraid of radioactivity. We today, would be much more reasonable about the simple fact that we ought to have the strengths, but we ought to be very careful before using it.

Oral histories courtesy of John Bass at the Los Alamos National Laboratory.

Aeby’s color photo of the Trinity explosion on Wikipedia.

Video stills of the Trinity explosion, taken by Berlyn Brixner, the government’s official videographer

This documentary comes from Sound Portraits Productions, a mission-driven independent production company that was created by Dave Isay in 1994. Sound Portraits was the predecessor to StoryCorps and was dedicated to telling stories that brought neglected American voices to a national audience.

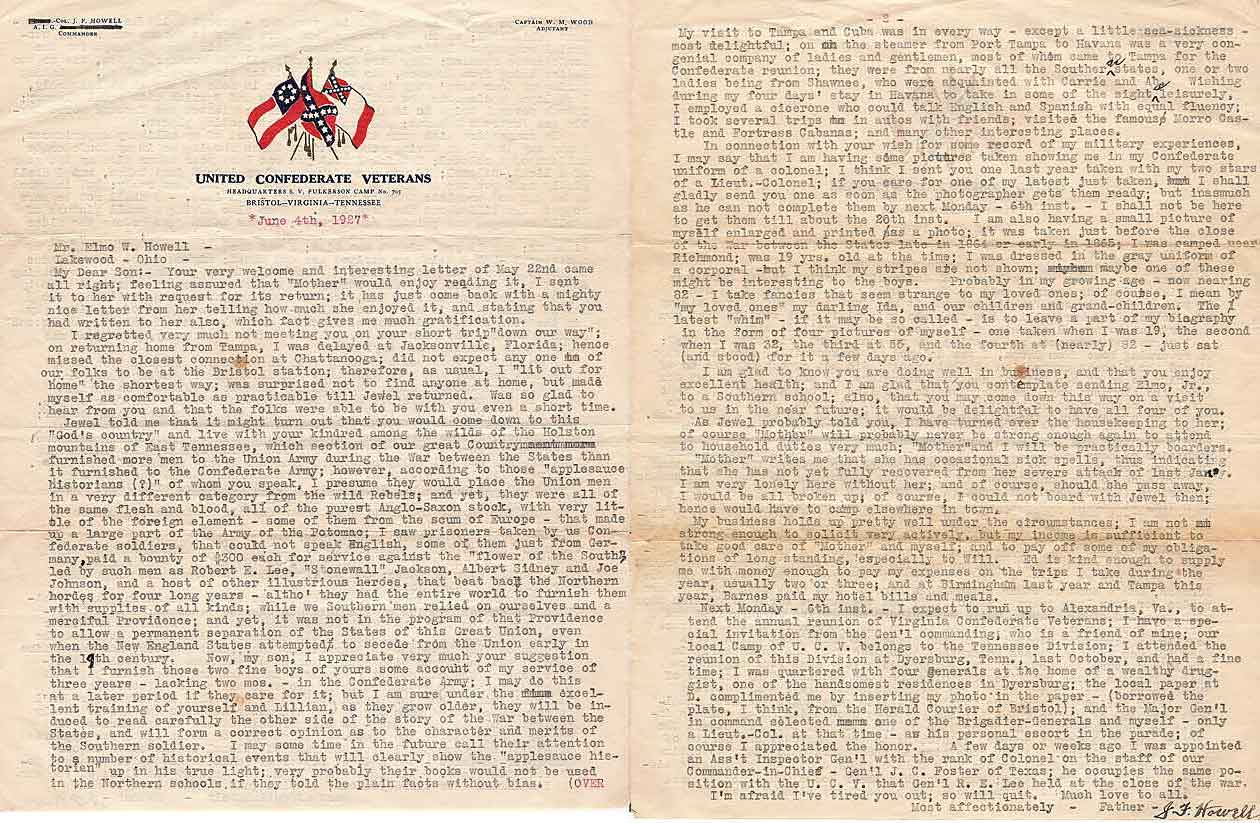

Julius Howell, Civil War General

Julius Franklin Howell joined the Confederate Army when he was 16. After surviving a few battles, Howell eventually found himself in a Union prison camp at Point Lookout, Maryland. In 1947, at the age of 101, Howell made a rare recording at the Library of Congress, in which he described his enlistment, sudden capture, and his experience in the Union prison camp on the morning of April 15th, 1865, the morning Abraham Lincoln died.

Recorded in Washington, DC. Premiered April 15, 2005, on All Things Considered.

A letter Howell wrote to his son

This documentary comes from Sound Portraits Productions, a mission-driven independent production company that was created by Dave Isay in 1994. Sound Portraits was the predecessor to StoryCorps and was dedicated to telling stories that brought neglected American voices to a national audience.

Red Mike’s Band

For more than 75 years trumpet player Red Mike Acampora has been a staple of New York City’s Little Italy. At one time his band worked a crowded schedule, playing religious festivals, block parties, and funerals. But over the decades, Little Italy shrunk to just over a city block. Most of the old neighborhood is now part of New York’s rapidly expanding Chinatown. Business for Red Mike’s Band would have all but dried up if not for the fact that the Chinese community adopted the tradition of Italian bands playing at their funerals.

Last week Red Mike passed away, at the age of 91. You’re about to hear a recording of the last time the band played together with Red Mike as leader, outside the Chinese Cheung Sang Funeral Home, on Mott Street.

Recorded in New York City. Premiered December 4, 2004, on Weekend Edition Saturday.

This documentary comes from Sound Portraits Productions, a mission-driven independent production company that was created by Dave Isay in 1994. Sound Portraits was the predecessor to StoryCorps and was dedicated to telling stories that brought neglected American voices to a national audience.

Barbers of Belmont

Hidden deep inside New York’s famed Belmont racetrack, below the grandstand and past rows of betting windows, is a plain sign tucked almost out of sight, which reads, “Barbershop.” There, inside a cavernous cinder-block room with three old-fashioned barbershop chairs, you’ll find the incomparable barbers of Belmont: Sal, Tony, and Uri.

Recorded in Elmont, NY. Premiered October 25, 2004, on Morning Edition.

This documentary comes from Sound Portraits Productions, a mission-driven independent production company that was created by Dave Isay in 1994. Sound Portraits was the predecessor to StoryCorps and was dedicated to telling stories that brought neglected American voices to a national audience.

Northlandz

Just off Route 202 in Flemington, New Jersey, sits an unimpressive warehouse that holds a most impressive life’s work — that of the husband and wife team Zaccagnino, creators of the world’s largest model railroad. Inside, scores of model trains wind their way past an unrelenting succession of impeccably detailed scenes in miniature — mini cities give way to mini mining towns, mini graveyards, even mini outhouses. In the center of it all, Bruce Zaccagnino plays a massive pipe organ, providing the soundtrack to this universe in miniature.

Recorded in Flemington, NJ. Premiered September 7, 2004, on All Things Considered.

This documentary comes from Sound Portraits Productions, a mission-driven independent production company that was created by Dave Isay in 1994. Sound Portraits was the predecessor to StoryCorps and was dedicated to telling stories that brought neglected American voices to a national audience.

George Stinney, Youngest Executed

On June 16th, 1944, the state of South Carolina executed George Stinney, Jr. He was fourteen years, six months, and five days old, the youngest person ever executed in the United States in the 20th Century.

Stinney, who was black, was convicted of murdering two white girls, Betty June Binnicker, age 11, and Mary Emma Thames, age 8, with a railroad spike. The trial lasted three hours, and the all-white jury deliberated for 10 minutes before sentencing George Stinney to death in the electric chair.

At Stinney’s execution six weeks later, the guards had difficulty strapping him to the electric chair (he was 5′ 1″ and weighed just over 90 pounds). During the electrocution, the jolt shook the adult-sized mask from his head.

On the sixtieth anniversary of his electrocution, one of the last surviving members of George Stinney’s family as well as the only living sibling of Betty June Binnicker recall the event.

George Stinney’s Prison Records (PDF, 435KB)

Recorded in Passaic, NJ. Premiered June 30, 2004, on Day to Day.

This documentary comes from Sound Portraits Productions, a mission-driven independent production company that was created by Dave Isay in 1994. Sound Portraits was the predecessor to StoryCorps and was dedicated to telling stories that brought neglected American voices to a national audience.

Remembering Kitty Genovese

On March 13th, 1964, one of one of the most infamous crimes in American history occurred in the Kew Gardens neighborhood of Queens, New York. At around 3 AM, 28-year-old Catherine “Kitty” Genovese was attacked, sexually assaulted, and murdered as she walked from her parked car. The assault lasted thirty-five minutes and occurred outside of an apartment building where a reported 38 witnesses either heard or saw the attack and did nothing to stop it. A front-page article in the New York Times sparked an avalanche of press and weeks of national soul searching. The case has lived on in plays, musicals, TV dramas — it even spawned a whole new branch of psychology.

Today the name Kitty Genovese remains synonymous with public apathy, although almost nothing is known of who she actually was. It was not reported in 1964 that Kitty Genovese was a lesbian and that she shared her home in Kew Gardens with her girlfriend, Mary Ann Zielonko. In this piece, the first broadcast interview she has ever granted, Mary Ann remembers Kitty and the time they shared.

Recorded in West Rutland, Vermont. Premiered March 13, 2004, on Weekend Edition Saturday.

This documentary comes from Sound Portraits Productions, a mission-driven independent production company that was created by Dave Isay in 1994. Sound Portraits was the predecessor to StoryCorps and was dedicated to telling stories that brought neglected American voices to a national audience.